SUGGESTED READ: Cocaine and Cooking at Chez Panisse

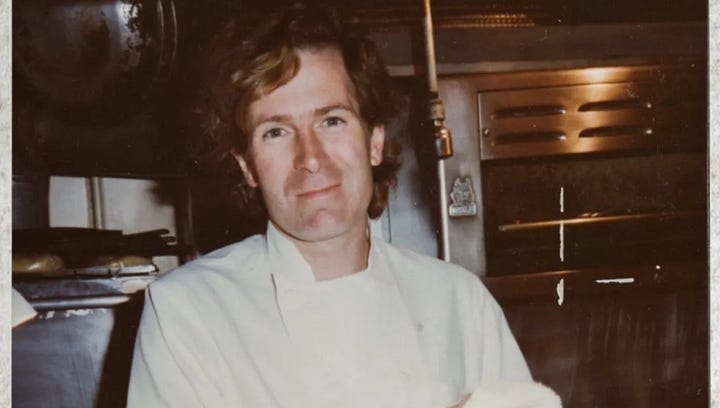

Jeremiah Tower's Out of the Oven is a new newsletter on SubStack

It was cocaine that became the fuel for the energy that changed the way America dines, and for the high-profile and all-consuming peripatetic schedules that launched the superstar chefs.

At Chez Panisse it started on the restaurant’s third birthday in 1974.

We planned an open house at five dollars per person. With wine included we needed something cheap to serve.

I had to come up with it fast since the poster for the party by David Lance Goines, one of Alice’s lovers, was about to go into production.

I grabbed a favorite cookbook, Jacques Médecin’s La Cuisine du Comte de Nice.

Soon the day arrived for me to tell everyone what a “Panisse” was and to order the ingredients. The recipe called for chickpea flour to be mixed with water and fried in olive oil. I drove down to my Italian delicatessen in Oakland, bought all the flour they had, and made a “Panisse.”

It was disgusting.

I decided to lie when anyone asked what a Panisse was.

“Basically, just a little pizza,” I said.

Alice and everyone else were happy with that. Pizza was what it had to be. Since we had no ovens that would cook regular-size pizzas, smaller individual ones were the way to go. What went on top had to be cheap and easy. I decided on a fresh California goat cheese (still new to the world in those days) and Sonoma beefsteak tomatoes, a fine idea until a hundred or so people more than we expected showed up and the cheese and tomatoes were gone.

In our walk-in refrigerators there were still fresh ingredients from the previous night’s bouillabaisse (clams, prawns, squid, crab, lobster, onions, saffron, garlic, and fennel), so I decided to scatter everything on top. What came out of the oven changed every hour depending on what was left, but little bouillabaisse pizzas they were.

Searches for ingredients caused delays, and soon a line formed to get into the kitchen. I was flagging a bit, and everyone was buying me champagne, which slowed me down even more. Word went out that the chef needed a boost.

In sauntered a friend of one of our waiters with a black-leather- coated accomplice. Flashing a gold-toothy smile as he glided by me, he pulled a plastic bag out of his coat. Then dumped half a pound of white powder on top of the chest freezer at the back of the kitchen. He cut it into several long lines and handed me a straw fashioned from a rolled-up twenty-dollar bill.

In an instant, I was back at the stoves. Then a conga line formed (this time not for the pizza), snaking out through the kitchen, into the dining room, and up the stairs into the bar.

The more consumption of drugs, the less demand for food.

Just before there was nothing left to cook, so that was good. And there was more cocaine and more champagne. The night was a huge success, premiering three new trends: individual pizzas, the freedom to use any topping one wanted, and the drug that made all the long hours possible, then impossible, in the kitchen.

In the following year, as our cocaine intake got out of hand, I would think someone on the staff was in love with me; my Beatnik sous-chef Willy would be stone broke and more interested in scoring than cooking.